Dan Gillmor writes a list of 22 ideas that would improve journalism (or, more accurately, “journalism”) as it’s practiced today. As with any such list, some are more essential than others. A few of my favorites, not necessarily in order:

We would not run anniversary stories and commentary, except in the rarest of circumstances.

Every day is the x-th anniversary of y. This fact, in and of itself, does not require the fraction of the print-hole currently devoted to reminding us of this. In the internet era, in fact, such practice is less than useless. The 100th anniversary of the end of WWII, and other such seminal, big-number dates do still demand at least some backward looks, but daily papers likely aren’t the place for that either, unless they decide to go long-form and really provide something unique. The ease in producing them coupled with a (seemingly) disdainful regard for their readers’ needs perhaps explains why they choose to roll out such vacuous, culturally debatable, and ultimately banal looks back at the Summer of Love (and etc…) when coupled with the Baby Boom generation’s apparently endless reserve of self-regard (and their eternal willingness to pay for ever more talismen of group identification) are probably prime drivers here. It should stop here and now. Likewise such practices as the news weeklies’ semi-annual “Jesus” issues.

Close second in terms of annoyance: the empty trend piece. More and more people are complaining about the frequency of anniversary-based reporting…

The known knowns, and the unknown knowns:

[…] every print article would have an accompanying box called “Things We Don’t Know,” a list of questions our journalists couldn’t answer in their reporting.

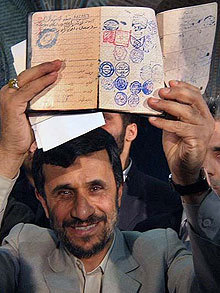

God almighty, this may be the most important one. Certainly such a policy would damn near put Lemkin out of business. Context should be king. Would that we had a media that didn’t aim merely to terrify instead of inform. Then we might actually have a sane national discourse on Iran, among many others.

The next two seem pretty much different sides of the same coin:

We would refuse to do stenography and call it journalism. If one faction or party to a dispute is lying, we would say so, with the accompanying evidence. If we learned that a significant number of people in our community believed a lie about an important person or issue, we would make it part of an ongoing mission to help them understand the truth.

We would replace PR-speak and certain Orwellian words and expressions with more neutral, precise language. If someone we interview misused language, we would paraphrase instead of using direct quotations. (Examples, among many others: The activity that takes place in casinos is gambling, not gaming. There is no death tax, there can be inheritance or estate tax. Piracy does not describe what people do when they post digital music on file-sharing networks.)

This is way up there, though it implies an outsized influence of print journalism…perhaps such a policy would filter into television and internet media, perhaps not. Anything done to reduce the repeating of either party’s talking points and scare lines, even just in print media, would be worth doing. Even if it does nothing to the larger discourse, we’d at least have a little bubble of rational discourse out there for people to find when they tired of the idiocy that is TV news and talk radio.

Which leads us to:

If we granted anonymity and learned that the unnamed source had lied to us, we would consider the confidentially agreement to have been breached by that person, and would expose his or her duplicity, and identity.

Yes, yes, a thousand times: yes. This alone would fix much of what ails the modern political MSM. Quite simply: Karl Rove could not have existed in an environment like that.

Which brings us to a real innovation in the sense of combining the limitless capacity of the web with the inherently limited capacity of the daily paper:

For any person or topic we covered regularly, we would provide a “baseline”: an article or video where people could start if they were new to the topic

You’d free more space in the paper for analysis of the topic at hand (by moving the background into the baseline piece) and be able to provide a hell of a lot more baseline as well. Excellent idea. The New York Times could, if it chose to, absolutely dominate the baseline industry without much of an investment. They choose not to, apparently. They do so at their peril. Somebody will do it, and soon.

Finally:

We would never publish lists of ten. They’re a prop for lazy and unimaginative people.

Agreed. This is precisely why Lemkin posts Lists of Four.