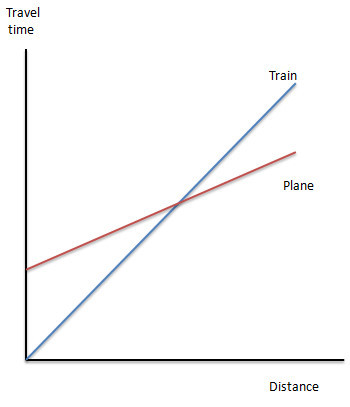

Suppose that I put those fixed costs at 2 hours; suppose that planes fly at 500 miles an hour; and suppose that we got TGV-type trains that went 200 miles an hour. Then the crossover point would be at 667 miles. It would still be much faster to take planes across the continent — but not between Boston and DC, or between SF and LA.

This is just so obviously right, and furthermore strikes me as a prime example of how policy should get made (but too rarely is): empirically. Figure out where those lines cross and then heavily fund everything pre-cross. Just flat out eliminate all other passenger rail until demand is measurably there to support it (ascertained via the same type of calculation). Then the GOP could actually make sense (for once) when they agitate for Amtrak to make money or be eliminated. Instead, they force a vast array of unprofitable routes on it, put the whole of Amtrak’s financial outlook on the back of the northeastern corridor, routinely underfund or defund infrastructure in said corridor, and then wonder why service is relatively slow there and insufficient to turn a profit for the whole rest of the system.

And but also I really think the reflexive GOP train opposition boils down to 1) they perceive it as something that reliably pisses liberals off –and– 2) white suburban conformists in the vast not-the-northeast part of the country just can’t fathom how hard it can be to drive anywhere, much less to set out on the Interstate and face traffic like the western US experiences only in city centers and only at rush hour for the whole X-hundred mile trip. This makes the train seem like the best possible option for many shorter trips. Add that to a predilection for destination cities in which a car is not only unnecessary, but can even be a hindrance and then the true shape of this policy disconnect takes form:

The west sees trains as steam powered slowpokes that drop you off and leave you walking great distances in decidedly pedestrian unfriendly settings. The east sees trains as efficient (and often faster) conveyances that drop you off exactly in the middle of everything, with easier access to the places you are most likely going than you could ever hope to achieve by car.

In this way, both side can’t even fathom the position of the other…and the folks out west go so far as to studiously avoid the train systems when they come east. Even when they move here, they tend to gravitate to the farthest exurb they can find and drive everywhere. This usually boils down to inchoate fear of something with which they have no frame of reference, a well marinated and studiously husbanded fear of the “inner cities,” or just a simple sense of “you drive to work” because that’s what they’ve always done. But, trust me tourists: if you can navigate Boston by car, you sure as hell can use the T. And, as a bonus, you are much more likely to survive.